Assignment 8: Induction

1. Prove or disprove the claim that there are integers m, n such that

Proof: Let n = 0. Then

2. Prove or disprove the claim that for any positive integer m there is a positive integer n such that

Proof: For any positive integer m, let n=m+2, then

3. Prove that there is a quadratic

Proof: Let b=2 and c=1. Then

4. Prove that if every even natural number greater than 2 is a sum of two primes (the Goldbach Conjecture), then every odd natural number greater than 5 is a sum of three primes.

Proof:

5. Use the method of induction to prove that the sum of the first n odd numbers is equal to

Proof: We need to prove

For k=0, the left-hand side is 1 and the right-hand side is

Assume the identity holds for k. So

6. The notation

Proof: By induction.

For n=1, the left-hand side is 1 and the right-hand side is

Assume the identity holds for n. So

OPTIONAL PROBLEMS

1. In the lecture we used induction to prove the general theorem

There is an alternative proof that does not use induction, famous because Gauss used the key idea to solve a “busywork” arithmetic problem his teacher gave to the class when he was a small child at school. The teacher asked the class to calculate the sum of the first hundred natural numbers. Gauss noted that if

then you can reverse the order of the addition and the answer will be the same:

So by adding those two equations, you get

and since there are 100 terms in the sum, this can be written as

and hence

Generalize Gauss’s idea to prove the theorem without recourse to the method of induction.

Proof: Assume that

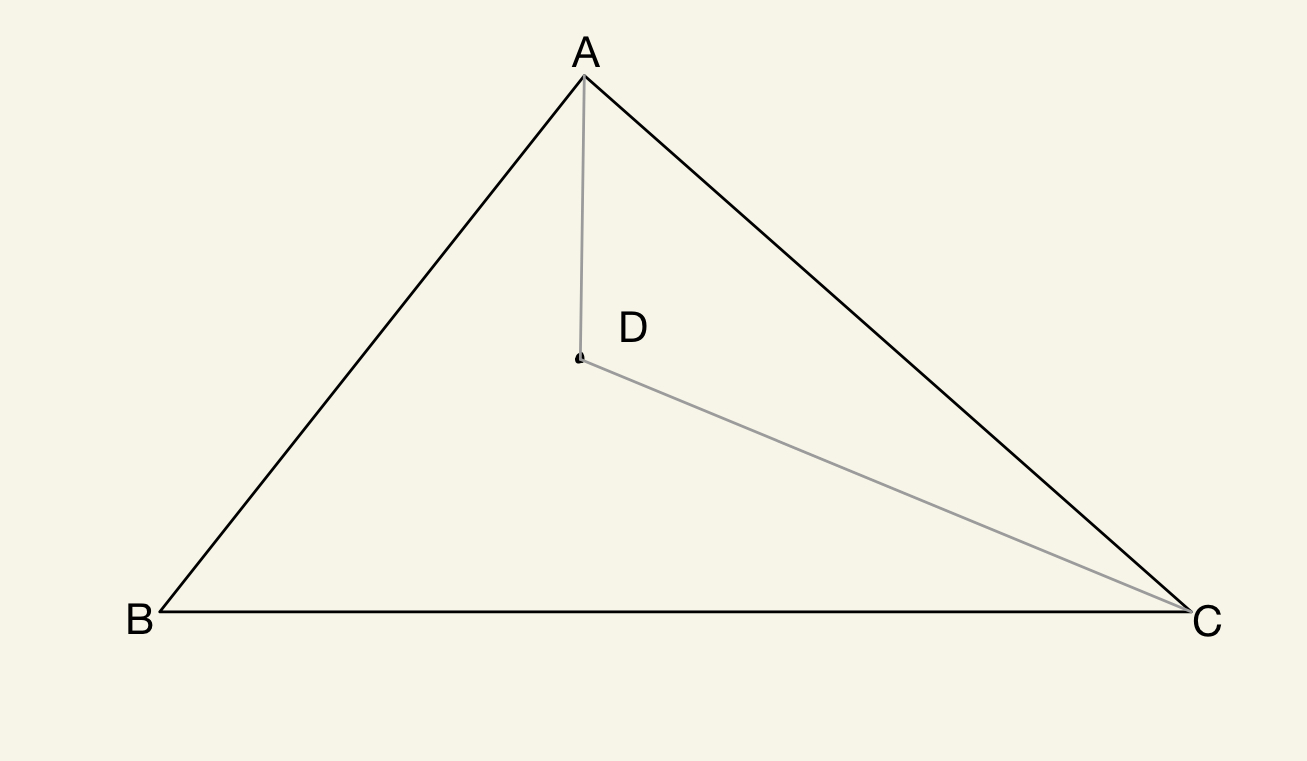

2. Prove that for any finite collection of points in the plane, not all collinear, there is a triangle having three of the points as its vertices, which contains none of the other points in its interior.

Proof: By contradiction.

Assume that for any finite collection of points in the plane, not all collinear, every triangle having three of the points as its vertices contain at least one point in its interior. Now we can easily construct a counterexample to our assumption. We construct a triangle having three vertices labeled A, B, and C, and a point D in its interior.  Now we connect the point D and the point A, and at the same time, we connect the point D and the point C. After that, we get a new triangle with three vertices A, D, and C. But there is no points inside the new triangle which contradicts to our assumption. And hence our assumption is false. Therefore the original statement is true.

Now we connect the point D and the point A, and at the same time, we connect the point D and the point C. After that, we get a new triangle with three vertices A, D, and C. But there is no points inside the new triangle which contradicts to our assumption. And hence our assumption is false. Therefore the original statement is true.

3. Prove the following by induction:

(a)

Proof: We need to prove that

For n=1,

Assume the identity holds for n. So

(b)

Proof: By induction.

For n=5, the left-hand side is 720 and the right-hand side is 256, so the inequality is valid for n=5.

Assume the identity holds for n. So

(c) ∀n ∈ N :

Proof: By induction.

For n=1, the left-hand side is

Assume the identity holds for n. So